Illuminating the Past: The Lincoln-Douglas Debates

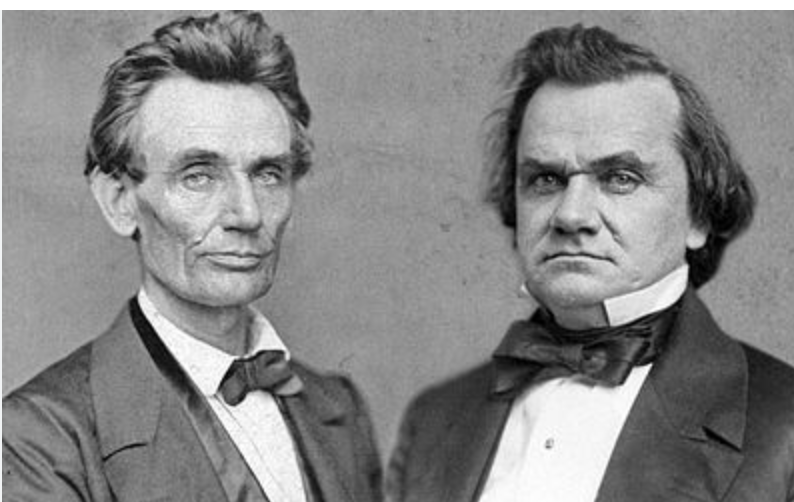

In 1858, the United States was on the brink of civil strife. The topic of slavery had become so much a dividing issue between the North and South. Against this volatile background, an absolutely unknown Illinois lawyer and politician, Abraham Lincoln, and one of the most famous and powerful senators of his day, Stephen A. Douglas, challenged each other to a series of debates that went beyond the mere rivalry for an Illinois Senate seat. Instead, it would plunge deep into the very soul and future direction of this country.

The development of Abraham Lincoln from an autodidactic lawyer into a great statesman, who signified the way to emancipation, is an evolution in moral and intellectual growth. His arguments in the debates revealed a depth of opposition not just to the spread of slavery but to the understanding of American values. The core of Lincoln's rhetoric laid in his belief in the inherent rights of all, drawn from the Declaration of Independence. This is to put forth that it was morally incompatible with a bedrock principle of the country. His vision extended beyond the abolition of slavery, touching on the regeneration of American democracy itself.

Stephen A. Douglas, in contrast, represented the complexities of 19th-century American politics. His advocacy of popular sovereignty—whereby any territory could decide for itself on the legality of slavery—was a pragmatic approach to the divisions within the nation. The stand of Douglas both politically was shrewd and revealed the moral ambiguities with which the nation had to reconcile itself with regard to the conciliation between its ideals and the practice of slavery.

His arguments were a part of a broader social conflict over where the balance of powers was to lie: between the states and the federal government, to be decided in the Civil War. The debates themselves were a spectacle of public discourse, attracting thousands of spectators and influencing far greater numbers through newspaper reports and transcriptions.

Ottawa and Freeport: At Freeport, Lincoln confronted Douglas with the Freeport Doctrine. Hence, he made Douglas work out a partnership between popular sovereignty and the Dred Scott decision, exposing the contradictions within Douglas's answers.

From Jonesboro to Charleston, in almost every debate, Lincoln's ability to integrate the moral opposition to slavery with the economic and social texture of American society was well evidenced. He spoke of how the extension of slavery imperiled not only social but also economic bases of free labor and democracy.

Galesburg, Quincy, Alton: The closing debates underscored escalating tensions, as Lincoln would lay out a vision for a country united in its opposition to the spread of slavery, dramatically different from the Douglas version, which was much more muddy and regionally qualified.

Although Douglas won and kept his Senate seat, the debates carried further and may have contributed to making Lincoln a national figure, in turn opening up the road to his bid for presidency in 1860. Still more, they revealed the ideological and moral breach, which had been starting to riddle American society, and foreshadowed the bloodshed that would follow.

The debates were something of a turning point in the history of this country, for the issues of slavery and the future of the Union were debated in the hearts and souls of the American people. The role of the media in disseminating the debates across the country cannot be overstated. It was the newspapers, the telegraphy, and the expansion of the railway that made the arguments and themes more of a national conversation than a local one, and changed the debates from local political rivalry into a national dialogue about slavery, democracy, and American identity.

Works Cited

“Lincoln-Douglas Debates - Background, Summary & Significance.” History.Com, A&E Television Networks, www.history.com/topics/19th-century/lincoln-douglas-debates. Accessed 8 Apr. 2024.

“The Lincoln-Douglas Debates of 1858.” National Parks Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, www.nps.gov/liho/learn/historyculture/debates.htm. Accessed 8 Apr. 2024.

“Lincoln-Douglas Debates.” American Battlefield Trust, 27 Feb. 2024, www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/lincoln-douglas-debates.

“Lincoln-Douglas Debates.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, inc., 28 Mar. 2024, www.britannica.com/event/Lincoln-Douglas-debates.

Written by Imad Shaikh from Houston, Texas. Imad was a program management intern in Winter 2024 at Eloquence Academy.